6th-order jerk-controlled motion planning

-

@larzarus yours is a very interesting experience, which suggests me that there is still invaluable desirable effects on this S-Curve implementation. Beyond printing speeds, the hardware in the printers will be less exposed to wear and tear and the expected hardware life will increase. Also maintenance cycles will be lower. With less vibrations bolts will not become loose and steppers will not have to absorb the vibrations.

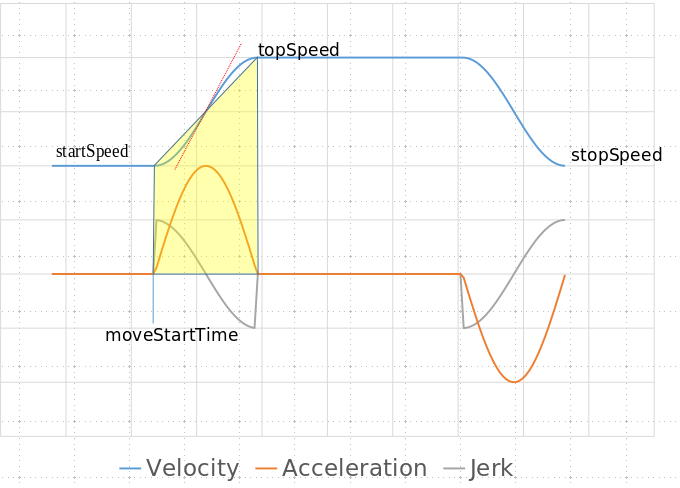

I have read the Movement code and it seems that DriveMovement.cpp also uses a trapezoid. There are references on the code to an "Acceleration phase", " Constant speed phase" and "Deceleration phase". In an analogy with TinyG implementation, they make a sub-division of the same trapezoid into 5 segments: First and second halves of the acceleration ramp (the concave and convex parts of the S curve in the "head" or "Acceleration Phase" in Duets movement.cpp"). Periods 3 and 4 are the first and second parts of the deceleration ramp (the tail), or "Deceleration phase" in Duets Movement.cpp. There is also a period for the "Constant Speed phase".

I wanted to give it a go, but adding this feature requires far more knowledge of the actual implementation that I have and the leaarning curve will take time. I am willing to help, but I would need the guidelines of the code maintainters.

-

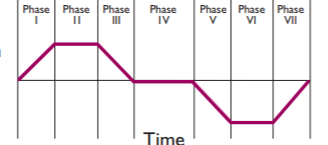

To do it properly you need to limit the acceleration and deceleration. So the acceleration and deceleration phases need (in general) ramp up, constant acceleration/deceleration, and ramp down phases. That's 7 phases per move.

-

I've got mixed feelings about the benefit for normal use. I was doing experiments to push the limits of my machine. If you routinely run your machines close to its limits (extruder, mechanical, etc), then yes, definitely worthwhile and 'something for nothing' (except programmer effort!). I used it daily for well over a year with good results, squeezing some extra performance from my rig. Switching to the DuetWifi, I dialed back the speed and accel, but for daily use I don't really I miss it much. Would I use it if it was there? Sure. But it's a fringe nice to have, not a core requirement.

In terms of nitty gritties, I kept the 'phases' the same in the Marlin motion planner -- the 3 phase trapezoid of accel, coast, dec. To implement the sinusoidal jerk, I injected some code into the pulse generator loop, where the accel phase had a function of speed = speed + accel (similarly speed = speed - accel for dec phase). I replaced the accel term with a fixed-point math lookup table of a pre-generated sine curve** (multiplied by accel). The table has an almost-linear section in the middle, effectively making for three blended sub-phases (net 7 motion planner phases, as dc42 is refers to).

This shaped the accel and dec sections of the trapezoid into the desired s-curve. I wouldn't say it's proper by any means, but it was achievable on the 8 bit cpu in terms of performance and without an entire rewrite of the motion planning codebase. A quick hack, enough to test if s-curves provided any benefit...It did result in smoother movement (less violence / oscillation and quieter), allowing me to increase acceleration, which increased net average speed per segment.

I'm sure dc42 has a very clear picture of what would be needed to implement it: certainly a more correct, complicated and involved effort than my tests. There is a definite benefit, for some, but is it worth the effort? Dunno.

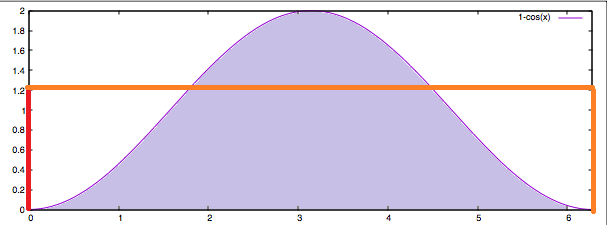

** taking care that my pre-generated curve maintained the same 'area under the curve' integral as the instantaneous jerk / line accel would, so the resulting phase resulted in the same total number of movement steps (at least to the limits of the fixed point math the wimpy 8 bit cpu is capable of)

-

Hi, I am trying to do some progress with this. Las post from Lazarus was very clarifying and opened some ideas that I have been exploring. I would like to share with the forum the process to add some light to the maths behind the algorithm so that I can get closer to an implementation.

The first thing that called my attention from Lazarus' last post was the use of sinusoidal functions to generate an S-Curve. It triggered a lot of crazy ideas to use signal processing algorithms to work on the frequency domain, so I crushed the numbers. Unfortunately the sinusoidal waveforms do not meet the requirements.

Which are the requirements that the ideal S-Curve shall meet?:

- It shall have acceleration=0 (dv/dt =0) at the joints of the trapezoid.

- lt shall have jerk =0 at the joints of the trapezoid (dv/dt2 =0 ).

- It shall fit on the control points to the trapezoid acceleration and deceleration phases.

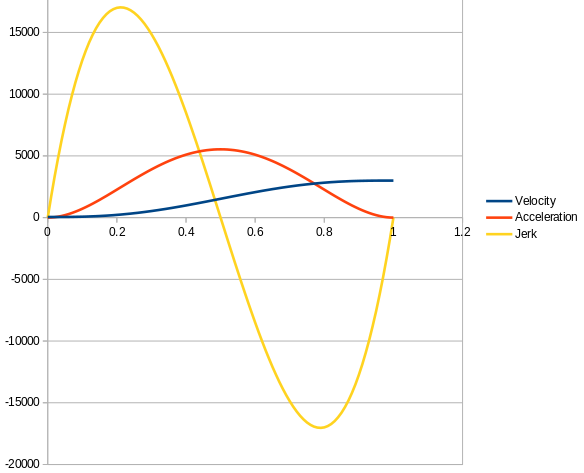

Sinusoidal waveforms can fit the trapezoid and have zero acceleration on the joints, but will fail on jerk. The maths behind this: If we use sin(t) to generate the shape, its derivative cos(t) will start and stop at 0, but its second derivative -sin(t) will not. the following graph shows an example on a Spreadsheet of Velocity, Acceleration and Jerk using sinusoidal waveforms where jerk is celarly non-zero on the trapezoidal joints:

Sadly I had to abandon the idea to use sinusoidal waves and started looking at the Bezier curves, but realized that not all Bezier curves could be fit to meet the requirements and at least a fifth order Bezier curve is required is we want to assure jerk=0 and higher orders would ensure also snap crack or pop. Since Bezier curves can be derived to infinite, it is a matter of increasing the order. However the mathematical complexity is probably not worth to compensate some effects that are physically hard to understand (I see them as harmonics of low effect). With a fifth order Bezier we can express the velocity in function of time with the following formula:

- V(t) = At^5 + Bt^4 + Ct^3 + Dt^2 + E*t + F

Where t is normalized time (from 0 to 1). And the challenge is to solve the weights (A,B,C,D,E,F). For this we apply the constraints

-

Constraint #1: dv/dt =0 at t=0 produces the first solution E=0.

-

Constraint #2: dv/dt2 =0 at t=0 produces the second solution D=0

So having E0= and D=0 warrants a jerk-free curve on the joints. -

Constraint #3: fit the curve to start speed and top speed.

-

Constraint #4,5: force dv/dt=0 and dv/dt2=0 at t=1 produce other equiations that combined will solve to the final result.

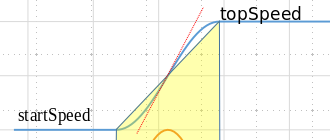

A = -6*initialSpeed + 6*endSpeed B = 15*initialSpeed - 15*endSpeed C = -10*initialSpeed + 10*endSpeed D = 0 E = 0 F = initialSpeed

On the Acceleration Phase

initialSpeed=startSpeed

endSpeed=topSpeedOn the decceleration phase

initialSpeed=topSpeed

endSpeed=stopSpeedThe same formula applies, but if startSpeed is different that stopSpeed, the coefficients need to be recalculated to fit the trapezoid properly.

The following graph shows the graphical representation of the S Curve, acceleration and jerk using the brute force calculation on a Spreadsheet of the formula (i used startSpeed=50 and topSpeed=3000):

So these are the maths and are not so complex once understood. Now the challenge is the implementation. For that I have been reading the implementation of Movement in ReprapFirmware (and I will have to read another dozen times before I get comfortable with it and attempt to do any attempt to modify anything), so far, what I have understood is the following (and the experts can correct me if I misunderstood the code):

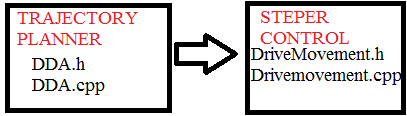

DDA.cpp deals with the motion planning.

DDA::Init(): would require a call to a function that calculates the coefficients of the S-Curve (A,B,C,F) each time there is a new value for "Startspeed","topSpeed" or "endSpeed".DriveMovement.cpp

DriveMovement::CalcNextStepTime() contains the loop that define the frequency of calls to the ISR interrupts in nextCalcStepTime.

This is defined as follows for a cartesian printer:// acceleration phase

const uint32_t adjustedStartSpeedTimesCdivA = dda.startSpeedTimesCdivA + mp.cart.compensationClocks;

nextCalcStepTime = isqrt64(isquare64(adjustedStartSpeedTimesCdivA) + (mp.cart.twoCsquaredTimesMmPerStepDivA * nextCalcStep)) - adjustedStartSpeedTimesCdivA;I am still having trouble to understand this (it is a big challenge for me!), but looks like it is calculated as a function of A (meaning Acceleration?). If this is the case, it would be a matter of adding an "if (trajectoryPlanning=bezier) { nextCalcStepTime = a_function_of_the_variable_S_Curve_velocity_in_realtime}.

[the if... would allow to define an M code and make the feature configurable]

Another "major" challenge to reach the goal is too find a method to calculate v(t) [or (a(t)] in an efficient manner for a real-time system.

TinyG is using "Forward Difference Calculation" algorithm. Forward differencing is an efficient scheme for evaluating a polynomial at many uniform steps, but it will not work if the steps are not uniform.

Marlin is tickless, i.e., interrupts are only generated where a step (or some other event) has to be scheduled. Because of this Marlin implementation could not use TinyG approach and their solution consisted to transform the math to use fixed point values to be able to evaluate it in realtime and they implemented this portion in assembler code to be even more efficient.In the case of Duet, I need to read further, but would appear that it is also tickless. We might explore other algorithms (probably we could not do better than Horner's method) or adopt Marlin's approach.

It's been a long post, but I would hope that it is useful and leads us to a successful implementation of a new feature that is already receiving lots of recognition by the Marlin community.

Carlos.

-

@carlosspr Take a look at this article: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6539/02c3dbd1aa7afe4d5f3538524de149d4ecb2.pdf It explains how to achieve the desired 0 jerk / 0 accel at the crossover points. It's also got some empirical data on resulting forces and movement execution time, showing the benefit in quantifiable terms. It's worth the read.

-

I have been following this discussion, and improving the motion algorithm is on my list.

The Marlin implementation assumes zero acceleration at the start and end of each segment, and I think it also assumes zero rate of change of acceleration at the start and end. This is reasonable for a travel move on a printer with non-segmented kinematics. However, when accelerating over a number of segments, we definitely do not want to start and end with zero acceleration, we want uniform acceleration across several segments, except at the start and end of the acceleration. Otherwise the motion will be jerky, for example at the start and end of the outline when printing a cylinder.

So at present I favour traditional S-curve motion (3rd order motion profile). See https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a229/fdba63d8d68abd09f70604d56cc07ee50f7d.pdf. But before I make a decision, is anyone reading this thread aware of any evidence that higher order motion profiles are advantageous?

-

@dc42 yes, symetric higher motion profiles like trigonometric functions or Bezier curves are advantageous. They simplify the implementation greatly and do not require to change the planner. I will elaborate.

Third order moves is quicker to calculate, but would require recalculating the planner variables like "accelDistance" and "accelDistance" and it would require many changes in DDA.

The beauty of Marlin/TinyG implementation or sinusoids (versus parabolic) is that the area under the S-curve is exacly the same as using the constant acceleration model. This is because the areas above and below the equivalent linear speed are equal and it allows to use the calculations and planning as if it was a constant acceleration move. To illustrate this check the next figure: the blue line is the speed versus time. The distance traveled from startSpeed to Top Speed is equal to the area of the yellow figure, which is the area used to plan movements using constant acceleration.

So basically Marlin does not change the planner "at all". Only when they calculate the step pulse frequency, they use a Bezier curve to evaluate the time to the next steps on the acceleration and deceleration phases versus using a constant acceleration.

Traditional 3rd order motion profile (like the parabolic profile on the paper) is not a mathematically complete solution. It will also produce zero acceleration at the start and end of a segment, but the difference with Bezier curves is that it does not assure zero jerk. On the paper the "Figure 5. Parabolic profile" shows the velocity and acceleration, but not the jerk. The jerk is the derivative of the acceleration which can be seen as the slope of the tangent at each point of the curve. For this figure 5 the jerk will be constant (no zero) in all joints.

From a mathematical point of view, and ease of implementation, Bezier curves are the perfect solution and at the end a simpler approach.

-

Like I said, the Marlin implementation only works because it assumes zero acceleration and jerk at the start end new of each move - and that assumption will have nasty consequences. Once you drop that constraint, Bezier curves lose their appeal.

-

@dc42 just playing with the implementation on Duet, this might give some ideas:

on Drivemovement.h I have declared new variables on the struct PrepParams as follows:

// Bezier coefficients for the acceleration phase float bezier_aA; float bezier_aB; float bezier_aC; float bezier_aF; bezier_aNormalizeTime; //required to normalize time between [0,1] // Bezier coefficients for the deceleration phase float bezier_dA; float bezier_dB; float bezier_dC; float bezier_dF; bezier_dNormalizeTime; //required to normalize time between [0,1]The reason to have duplicated coefficients is that Prepare is called once for the whole move.

These variables are evaluated on DDA::Prepareparams.bezier_aA = 6*(topSpeed - startSpeed); params.bezier_aB = 15*(startSpeed - topSpeed); params.bezier_aC = 10*(topSpeed - startSpeed); //bezier_D = 0 //bezier_E = 0 params.bezier_aF = startSpeed; params.bezier_aNormalizeTime =1/accelStopTime; //move starts at Time=0For the deceleration phase just replace startSpeed by topSpeed and topSpeed by endSpeed. params.bezier_dAV =1/(totalMoveTime - decelStartTime)

totalMoveTime does not exist in the current code and needs to be calculated (part of the work pending).On Drivemovement.cpp I have added a new function for the class DriveMovement that will calculate the instant velocity.

float instantVelocityBezierAccelerationPhase (const uint32_t currentTime) { // Instant velocity is defined by the formula // V(t) = At^5 + Bt^4 + Ct^3 + F // Implemented with Horner’s Method for Polynomial Evaluation // Polinomial coefficients are {bezier_aA,bezier_aB,bezier_aC,0,0,bezier_aF} // Current time shall be normalized between t=[0,1]. float t= currentTime*bezier_aNormalize; // this ensures time will be between 0 and 1 float result = bezier_aA; result = result*t + bezier_aB; result = result*t + bezier_aC; result = result*t*t*t + bezier_aF; return result;}

Finally, on CalcNextStepTime functions, for the Acceleration phase

nextCalcStepTime = 1/instantVelocityBezierAccelerationPhase(timeSinceMoveStart);I still have not figured out how to calculate "timeSinceMoveStart". I am reading the code many times and getting more and more familiar with it, but is hard for me as I am new to this firmware.

It has errors. For example instant velocity is float and nextCalcStepTime is defined as uint32_t, and is not complete.

it is necessary to define an M code to be able to select between actual linear velocity profile and S-Curve and add the corresponding "if" on the relevant sections.

Finally I have not evaluated performance and it is more than probable that we need modify the math to use fixed point values the same way marlin has done (https://github.com/MarlinFirmware/Marlin/pull/10337/files).

Let me know if I can help you.

-

@dc42 I do not see the nasty consequences.. Can you elaborate?.

I imagine this as a driving a car. I start the engine and start accelerating until I reach the maximum speed on the road (80Mps for the shake of the story). Then I maintain the velocity and to do that I do not apply any more acceleration to the car (acceleration =0). If I see a curve, I push the brake and reduce velocity a bit to 60Mps (decceleration) and at the exit of the curve I push the accelerator to increase speed again to 80Mps for the next road segment.

In this drive, there is an inflexion point when the car reaches the minimum speed and before it starts accelerating again (gains more velocity). If the movement is smooth the speed profile would be like a "U" with the minimum speed reached at 60Mps. On the bottom of the U, the tangent (acceleration) is horizontal and therefore the acceleration is 0, and this does not produce discontinuities or nasty consequences.Also a third order motion profile will have 0 acceleration at the start end new of each move and will have the same consequences so I see no differences (except for the fact that it will have jerk).

-

@dc42 said in 6th-order jerk-controlled motion planning:

...So at present I favour traditional S-curve motion (3rd order motion profile). See https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a229/fdba63d8d68abd09f70604d56cc07ee50f7d.pdf. But before I make a decision, is anyone reading this thread aware of any evidence that higher order motion profiles are advantageous?

@dc42 I'm gonna throw in this quote from the paper I linked to:

...the trigonometric S-curve trajectory is:

• simple as 3rd order polynomial model and

• capable of producing smooth trajectory as good as 5th order polynomial S-curves and quintic splinesThat's what drew me to this solution in my testing -- a close approximation of 5th order with only 3rd order effort, by replacing this angular jerk curve:

with a sinusoidal jerk curve -- I mean look at it, it's beggin' for it!

If you're considering limiting the implementation to 3rd order to keep it simple / maintain performance, this may be something easy and worth adding?

If you're considering limiting the implementation to 3rd order to keep it simple / maintain performance, this may be something easy and worth adding?Honestly, anything that get us away from instantaneous jerk is going to be the largest single improvement (even the simplest 3rd order will help).

Beyond that, the debate over what's the best way to shape higher orders (splines, trig, polynomials, etc) can go on forever, and no answer will please everyone. I don't know how reasonable it is, as this is deeply tied into everything motion planning, but maybe consider if it's possible to encapsulate that shaping math enough that others can plug in their favorite method? You know, to get people off your back.

-

@larzarus, in the particular example you give, sinusoidal acceleration would indeed be a close approximation, although it would be computationally much more expensive unless the sine curve can always be generated by a lookup table. However, if you imagine the same profile but with phase II and phase VI much longer than phases I, III, V and VII then it will look nothing like a sine curve.

I think all the papers about movement profiles that have been quoted in this thread assume point-to-point movement, i.e. whatever we are trying to move starts at rest at one point, and we want to move it to be at rest at another point as fast as possible without exceeding acceleration and velocity limits, and with jerk controlled to reduce the tendency to excite vibrations. So the velocity and acceleration start and end at zero. Although most travel moves in 3D printing fit this profile, many printing moves do not.

-

@dc42 Zero acceleration at the end points is shown in many examples, but it is not a requirement of this approach. Jerk is zero at the end points (a good thing) but acceleration at the start and end of the segment can be any value.

The sinusoid function is applied to jerk, which will result in a graceful s-curve acc instead of an angular one. You can still calculate all seven phases separately, with the sine function only being applied to jerk when jerk !=0. The only difference to the normal 3rd order calculation is instead of calculating linear jerk (a = a + j *t) for phases I, III, V, and VII, you apply the sine scalar multiplier (half sine wave on each phase) to the j term. Phases II, IV, and VI stay linear (jerk = 0) and be as long or short as necessary.

Yes, sine is a lookup table (one quarter cycle is enough, as you can flip it and/or invert to get the entire curve as needed)

-

I really do like the approach of the sinusoidal functions. Is a good trade-off between desired effect and computational cost.

Just one thought: Is it worth dividing the movement on 7 phases or just 3 would be sufficient?. The reasons are the following:

-

As Lazarus correctly mentioned on a previous post, applying a sine scalar multiplier would have an almost-linear section in the middle, effectively making for three nicely blended sub-phases (net 7 motion planner phases, as dc42 is refers to) with less planning effort.

-

The sinusoidal approach is based on constraining the Acceleration time according to the equation [1] on the paper provided by Lazarus to T=(max Acceleration)*pi()/(max Jerk) so that jerk is zero on the joints. Maximum acceleration and maximum jerk are configurations parameters for the printer. Adding more phases/joints where this constraint needs to be met would probably limit/constraint the movement time to reach top speed, while the existing 3 phases movement would do the same with only one joint constraint.

At the end, maximum acceleration and maximum jerk are configuration parameters that can be tuned to obtain maximum performance, so that this is probably not a problem, but definitely facilitates the implementation.

Note that if acceleration is defined in mm/s2, jerk here is defined in mm/s3.

-

-

I have been exploring the idea of a sinusoidal s-curve that can be generated easily lately, you can check a crude implementation of a three-phase sinusoidal speed profile: http://fightpc.blogspot.com/2018/05/one-table-to-run-them-all.html

I am not yet there, but I reckon with some work the idea of a look-up table (as Lazarus did) can provide accurate results with quick computation.

However, only long moves can show a significant benefit as for short ones the number of accelerating steps will make the s-curve approximation a crude one.

-

@carlosspr If you consider t-sin(t) expression for the speed increase you have a 1-cos(t) acceleration that will give you a smooth jerk at the speed corners.

A longer version with graphs that hopefully will show my point better:

http://fightpc.blogspot.com.es/2018/04/how-to-get-sinusoidal-s-curve-for.html -

@misan The basic principle in your blog is correct, but there are some constraints that need to be applied and they bring some complications to take into account.

You are modeling the acceleration as (1-cos(t)). The fists constraints to apply are:- Your motor is physically limited by a maximum acceleration (let’s call it Amax) and we would like to reach the maximum acceleration (if possible) to reach the travel constant speed in the shortest time.

- You might want to enter the segment with some initial acceleration (let’s call it a0)

Then you mathematical model for the acceleration becomes a(t) = a0 + (Amax-a0)(1-cos(t)).

Now we would lie a “jerk free” movement, therefore we need to apply another constraint and this is that the derivative of the acceleration shall be zero ant the beginning and the end of the acceleration phase. This gives you a limitation on the time for the acceleration phase

Tacc= Amaxpi/Jmax

This means that we cannot use the same trapezoid calculated for linear acceleration, where the acceleration goes from a0 to Amax instantly. For the trapezoids to be the same, the area under the graphs (this area equals the final velocity) shall be the same, this means that the sinusoidal model would “exceed” the maximum acceleration. I have used your graph to illustrate this:

Actually Marlin implementation using S-Curves has some benefits over the sinusoidal model:

- They use the same trapezoid logic used for instant acceleration model, thy know that they are exceeding the maximum acceleration configured on the firmware, and they are taking some risks here. The truth is that I have several Nema17 and I could not find manufacturer specs for maximum acceleration on any of the brands, and at the end of the day, the settings in my firmware are totally experimental,….

- Their model does not have the constraint of Acceleration time to obtain zero jerk that is required for sinusoidal models.

On my Ideal model I would also like to consider several use cases:

- Some movements are too short/fast and the Maximum desired kinematics (desired speed, maximum acceleration) can not be reached on the distance moved. This would impact/constraint the next segment with initial kinematics (final state of previous move), therefore the model shall consider to enter the segment with some initial acceleration and velocity.

- Some movements might ask for a travel velocity that can not be reached with a simple S-curve (we have a top on the maximum acceleration), and we the need to consider a "flat" acceleration phase until the travel speed is reached.

- Ideally physical constraints are specified by manufacturers and the firmware would respect them.

But it is also true that some approaches, even if the bend the rules (like Marlin and the Aceleration limit), might work easier and better on a real world. At the end of the day, if the model is so complex that it can not be implemented in realtime.... then is useless for now until future processors make them a reality.

-

@carlosspr I do agree motors have a limited torque, and therefore there is a limited acceleration they can produce. For stepper motors, the torque is maximum at low RPM and quickly goes down when motor speeds up (other motors do not have such a pronounced decay).

Static friction has to be overcome at the beginning of each motion with zero starting speed. Once motion is started, the dynamic friction is much smaller.

For a stepper motor, given the maximum speed we want to achieve, we go to the torque vs speed curve and choose, with a significant safety margin, the available torque at that speed. Please note that this is a very low value compared to what the motor is capable to deliver at slower speeds. But it is that low torque what we use to select our fixed acceleration for trapezoidal moves. If the value is too high, steps will be lost, so we chose it conservatively.

Conversely, if you can handle a variable acceleration, you do not need to keep that low value you calculated above for the worst case scenario, meaning motor can speed up faster and reliably.

My plan is to use the same trapezoid logic, with only 3 steps for the motion, with the difference that now acceleration and deceleration use variable acceleration instead of a fixed one (max accel is selected so accel time matches the same as a (smaller) fixed acceleration).

While I do agree the model has to consider non-zero initial or final speeds, I cannot say the same regarding acceleration, which I reckon should be zero at any joint between moves (but I am not sure about this entirely).

Trying to make it all possible in real-time with an 8-bit microcontroller is the reason I focused on working around a table-lookup, which is faster than an N-R solver.

I am still trying to understand Marlin's Bézier Jerk s-curve code.

The massive availability of torque of the steppers at low speeds is what made me think that an asymmetric acceleration s-curve could be a better fit (one with higher acceleration at the beginning instead of a pure symmetrical one like the sinusoidal curve). Of course, the logic would need to mirrored for deceleration.

-

I have finally managed to compile Reprapfirmware (had lots of problem with the ARM toolchain). I have tried to implement the S-Curve based in Bezier algorithm, but I cannot make it work.

I am posting here findings and reasoning to see if someone in the forum can see the errors and where it fails and/or clarify possible wrong concepts. i have the feeling that it might be related to unit conversions.... but I can not find the error.

There is not much documentation on how Reprap implements the Movement, so I have tried to understand it by reading the code. However, due to real-time optimizations the implementations are hard to follow and my findings can be wrong.

As far as I understood, the class Move controls all movement of the RepRap machine, both along its axes, and in its extruder drives.

The planner is implementer in DDA.h/DDa.cpp and the Control of the steppers in DriveMovement.h/Drivemovement.cpp

TRAJECTORY PLANNER (DDA): Implements a line tracing using Bresenham algorithm. In other words, it buffers movement commands and manages the movement profile plan. This ensure that our printer moves as fast as is possible within the kinematic constant constraints at the configuration.

This are the variables used by the motion planner to manage acceleration (defined in DDA.h).

float accelDistance; float steadyDistance; float decelDistance; float requestedSpeed; float startSpeed; float topSpeed; float endSpeed; float targetNextSpeed;All speed units are in mm/s

STEP CONTROL: The step control is performed at Movement.h and Movement.cpp. The process determines for each drive instants of the time t (in processor [cycles]) when pulses (steps) are generated based on the calculated profile.

There are two methods – two group of algorithms - for calculating instants of time when pulses must be generated. They are named as: “time per step” and “steps per time”. Reprap uses "time per step" with the following operation mode (as I could understand from the code):

- 1./ calculate time period to next pulse (nextCalcStepTime),

- 2./ wait until that much time period elapses,

- 3./ generate next pulse and

- 4./ go back to step (1) and repeat until desired number of pulses is over .

It is not very clear to me the algorithm followed to calculate nextCalcStepTime and I could see some compensation clocks on the formula which also I do not quite understand well.

In order to add an S-Curve profile, I followed Marlin approach to use the same trapezoid generated by DDA and only implemented changes in DriveMovement.

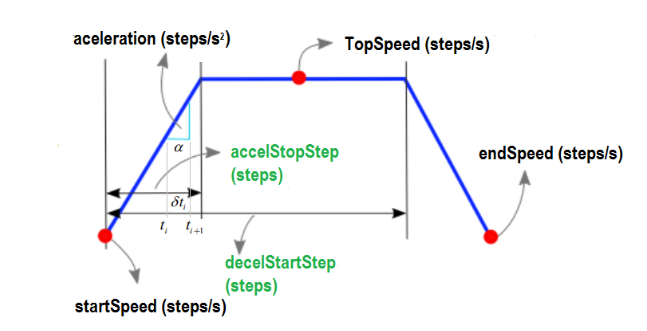

The first step I did was to draw the trapezoid using as speed units steps/s and the variables available in the code:

The trapezoid is the shape the speed curve over time in steps per second.

- It starts at step=0, accelerates until accelStopStep,

- then keeps going at topSpeed (constant speed) until it reaches decelStartStep

- after which it decelerates until the trapezoid generator is reset to next DDA at totalSteps.

The first pulse (step) controller generates at the start of motion, at the start of the phase of acceleration, i.e. at the step time t=0. After the first pulse is generated, the controller needs to calculate the time period until the next pulse (nextCalcStepTime) wait until this period has elapsed, and then generate the next pulse, at step time t=1. This will go on until the desired position is achieved, or in other words, the desired number of pulses (steps) has been generated.

Since after each pulse the motor makes one step of distance 1/stepsPerMm, the time delay between two successive steps is given by

*nextCalcStepTime* = 1 / ( stepsPerMm * V(t) )Instead of a linear speed in the acceleration and deceleration phases, V(t) is replaced by the quintic (fifth-degree) Bézier polynomial for the velocity curve:

V(t) = V_f(t) = A*t^5 + B*t^4 + C*t^3 + D*t^2 + E*t + FAnd this is calculated using the Bezier S-Curve with the same code developed by Eduardo José Tagle (Marlin).

The trapezoid generator state in DriveMovement.cpp contains the following information, that we will use to create and evaluate the Bézier curve:

accelStopStep [TS] = The total count of steps for this movement. (=distance) dda.startSpeed * stepsPerMm [VI] = The initial steps per second (=velocity) dda.topSpeed * stepsPerMm [VF] = The ending steps per second (=velocity) nextStep [CS] = count of steps completed(=distance until now or current step)In DriveMovement:Prepare, at the start of each trapezoid, I calculated the coefficients A,B,C,F and Advance [AV], as follows:

* A = 6*128*(VF - VI) = 768*(VF - VI) * B = 15*128*(VI - VF) = 1920*(VI - VF) * C = 10*128*(VF - VI) = 1280*(VF - VI) * F = 128*VI = 128*VI * AV = (1<<32)/TS ~= 0xFFFFFFFF / TS (To use ARM UDIV, that is 32 bits) (this is computed at the planner, to offload expensive calculations from the ISR) **/For the deceleration part, we use the same approach, but adapted to the initial velocity and final velocity of the segment:

* totalSteps - decelStartStep [TS] = The total count of steps for this movement. (=distance) * dda.topSpeed * stepsPerMm [VI] = The initial steps per second (=velocity) * dda.endSpeed * stepsPerMm [VF] = The ending steps per second (=velocity) * nextStep [CS] = count of steps completed(=distance until now or current step)Finally, in DriveMovement::CalcNextStepTime we calculate nextCalcStepTime for the S-Curve profile

nextCalcStepTime = 1 / (eval_bezier_curve(nextStep) * stepsPerMm); nextCalcStepTime = nextCalcStepTime * StepClockRate;The time is multiplied by the StepClockRate to get the number of clock cycles.

Probably I would need to add compensation Clocks.... but I do not understand why this is in the formula on the current firmware and could not test because it does not work properly.I could provide the Source code from DriveMovement.cpp and DriveMovement.h which are the only parts changed in case that anyone wants to investigate further......

-

It sounds that you have done some good work. The compensationClocks parameter is only used when applying pressure advance. So it is zero for ordinary axis movements, and zero for extruder movements if the pressure advance for that extruder is set to zero.